|

|

|

138 Squadron 1955 to 1962

by S.A.C. Rogers, Peter

This document is meant to provide a short and, if possible, authoritative account of the activities of 138 Squadron, when it was the first squadron in the RAF to operate as a V Bomber Squadron.

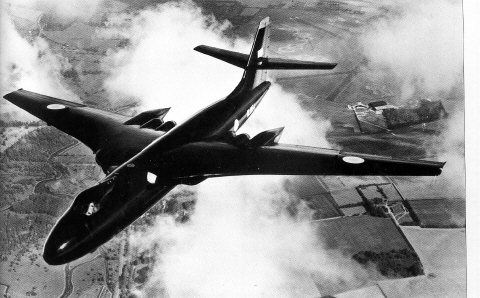

The V Bomber was of course, the Vickers Valiant, of which more later. My own interest in138 Squadron derives from the time I spent, as an Air Wireless Mechanic, during my National Service. I joined the Squadron in August 1955 at Gaydon, moving with it to Wittering, and remaining on the Squadron until I was demobbed in 1957.

Some of the information is from my own recollections, others from conversations with squadron members, both air and ground crew. During the narrative I have also drawn on facts and information from various publications which include:- “RAF Nuclear Deterrent Forces ‘’by Humphrey Wynne, “V Force” by Andrew Brooks, “Operation Grapple” by Hubbard and Simmons, and the wonderfully informative “Vickers Valiant, first of the V Bombers” by Eric B Morgan. I have also made use of the Squadron Operational Records at the National Archive at Kew.

It would be nice to know just how, and why, squadron numbers are allocated.

Why 138 was chosen as the pioneer squadron for the V force is not clear. It was of course a Bomber Command 3 Group squadron in its previous role, flying Lincolns until 1950. However, its’ main claim to fame, is as a wartime Special Duties Squadron. Flying Lysanders and Stirlings into occupied Europe and dropping off and picking up agents.

It may have been the Special Duties history that determined someone on high to decide that 138 should be the first V Bomber squadron. The squadron was formed in January 1955 at Gaydon, under the command of W/C R G W Oakley.

S/Ldr. Oakley, as he then was, had been the RAF liaison officer at Vickers during the aircrafts’ development. He succeeded S/Ldr Foster, who was killed when ejecting from the first prototype WB210 which was lost in an accident.

The first entry in the Squadron Operational Record Book (ORB) was in February 1955 and lists the C/O as W/.C, Oakley and a nil return for all other personnel. Shortly afterwards, other staff arrived and, on the 8th February, the ORB reports that; W/.C Oakley went to Wisley to collect the Squadrons’ first aircraft, which was WP 206. These trips to Wisley became regular occurrences during the Squadron’s first months.

The next entry in the ORB mentions staff beginning to arrive in all capacities, both air and ground. The captains listed were S/Ldr. Wilson, Flt/Lt’s Burberry, Mather and Flavell, and amongst the co pilots were Flt/Lt’s Steele and Millett.

It is reasonable to assume that the original captains had trained on the aircraft at Vickers before joining the Squadron. Flt/Lt LB Brown (Jock Brown), who was an original B flight captain, has confirmed that he flew the Valiant at Vickers before going to Gaydon. There is also mention of this arrangement in Humphrey Wynne’s work on the period.

The Squadron spent the early months converting crews and assembling ground staff. There was a certain amount of aircraft shuffling, as 138 operated PR versions of the Valiant destined for 543 Squadron. There was also a great deal of demonstrating the aircraft, with fly-pasts for the great and the good. These, eventually, were deemed to be deflecting the Squadron from more useful activity.

I remember Gaydon as a pleasant camp with reasonable facilities and food, but it is amusing to note the ORB mentions, that married officer’s and their wives were billeted in caravans at a local site.

In June the order came through posting the Squadron to Wittering where, of course, the bombs, or as the RAF preferred then, “special stores” were. Of course, we ‘erks’ never knew that in those early days.

An advance party set off on the 22nd June, and the rest of what was by now ‘A’ flight moved on the 6th July. The ORB shows that the aircrews were those of Oakley, Wilson Mather and Flavell. Senior ground staff included C/T’s Clayden, Seaman, Hetherington and F/S Barman.

Also on the advance party was Flight Sergeant Joy, an NCO who early members of the squadron will recall had a somewhat neanderthal approach to his role of squadron discipline NCO. On the arrival of B flight, in November 55, he became the victim of an organised campaign of resistance, which consisted of bombarding him with offers culled from newspapers. These ranged from Charles Atlas body building courses, to various surgical appliances and marital aids. As I recall, the co-ordinators of the scheme, who felt themselves to have suffered as a result of Mr Joy’s attentions, would come round on pay day collecting for the cost of any postage incurred. There were I suspect, few who declined to contribute.

Apart from the aforementioned display flying, the main thrust of the early flying programme was engine trials of the Avon engines. Toward the end of July in particular, the ORB notes that flying was concentrated on WP222, with it being flown by all the crews. However, as is now well documented, on the morning of 29th July, WP 222 crashed at Barnock, shortly after take off in an easterly direction. The accident enquiry concluded that a runaway aileron trim tab actuator caused the accident. The aircraft banked to port at 60 degrees before it struck the ground and exploded. It has been said that on early Valiants the trim switch was very close to the ‘press to talk’ VHF button and it might have been inadvertently actuated by one of the pilots. However, the court of enquiry concluded that the runaway was caused by a short circuit in the electrical supply to the trim tab actuator. Subsequently, steps were taken to ensure that the trim tab travel was limited on all aircraft. S/Ldr Chalk and his crew were buried with due ceremony in the Wittering Village Church.

On August the 28th 1955, ‘B’ flight began formation at Gaydon. Enter yours truly, fresh from Yatesbury. On 5th September, Operation ‘Too Right’ was undertaken by ‘A’ flight. This consisted of detatching two aircraft WP206 and WP207 on a proving, stroke flag waving, trip to Australia and New Zealand. The aircraft staged through Iraq , Pakistan, Ceylon and Singapore. The aircraft worked pretty well, although there was an engine change on WP206 and various problems with Green Satin and the STR18B HF radio. I can vouch that STR18 was pretty hopeless on the early aircraft although this was due to the aerial installation, more than the equipment itself. The trip was commanded by S/Ldr Wilson, who was O/C ‘A’ flight, and Flt/Lt Mather was the other captain. Ground staff were ferried around by Hastings, and the whole trip sounds redolent of the grand opinions we had of ourselves as a Nation at that time, as they staged through all those old Empire ports of call.

Meanwhile, B Flight was being assembled at Gaydon. One of the things I found both odd, and faintly endearing, about the Air Force in those days, was the scarcity of information about what you were supposed to be doing, and whom you were working for. My own case was typical.

I arrived from Yatesbury having completed the first Air Wireless Mechanic\V Bomber course. My first place of work was the Radio Servicing Flight (RSF) where I spent several days staring into space, and wondering what I was supposed to do. The attitude of the other bods there varied between, occasional interest in that I was then the first person that had actually been on a course on STR18, radio compass, ILS et al and complete indifference.

Then, for reasons I cannot recall, I was dispatched to a crew room at the western end of the airfield to carry out first line servicing on, by the standards of the day, these huge and almost frightening aircraft. I was allowed to join the tea swindle, surely a sign of acceptance, and spent most of the time talking to the chaps, as there was not a lot of flying .

It was only when I was “ issued “ to Chief Technician Keen, crew chief at that time of WP212, that I learned I was now on 138 Squadron. The Scotsman who emerged from the cabin, having flown the aircraft after it had major engine repairs, was the one and only Jock Brown, the pilot of whom it was said ‘he flew a Valiant like a Mosquito’.

During those days in the mid Fifties, when the country was still a fairly austere place, the Air Force, particularly the V force, seemed to enjoy a money is no object existence. So it was, that every aircraft on 138 had its own air and ground crew. Each crew chief had a full first line servicing crew; consisting of a rigger, engine mechanic, electrician, instruments, radar and wireless mechanics. At that time at Gaydon, the make up of the ground staff was about equally shared by a few grizzled veterans, (allegedly “difficult” people from other squadrons), national servicemen and fresh faced ex boys and apprentices.

The flying activities of ‘B’ Flight at that time were, it appears, connected with crew selection and training, but I also recall some formation flying for that years’ Farnborough Air Show. Needless to say, the ground crew were not informed.

On November 16th , ’B’ flight left for Wittering. Or rather the staff did. Bad weather meant that the aircraft did not arrive until several days later. From recollection, the information is not in the ORB, the aircrews were those of Sq/Ldr Collins, the flight commander, S/Ldr Clifton, Flt/Lt Steele and the aforementioned Flt/Lt Brown.

Arriving at Wittering was not a pleasant experience, compared with Gaydon, our accommodation was dire, as was the food , the dispersals and crew rooms. We slept forty to a room, in double bunks, on the ground floor of a four room barrack block, ‘A’ flight had already collared the two rooms upstairs. My mind has, I suspect, blanked out the toilet facilities available to us, but they were, let us say, no more than adequate.

The food was lousy, engendering a good trade for the NAAFI and the Malcolm Club; and the ‘B’ flight dispersals, as with ‘A’ flight, had no running water and Elsun toilets. Furthermore, we had the pleasure of encountering Flight Sergeant Joy, a new experience for me but not for many of my colleagues. This gentleman contrived to make what already seemed a bleak experience considerably worse. However as previously mentioned steps were taken to draw his teeth, and he retired in 1956 to be replaced by, the very different, Flight Sergeant Paddy Aldridge.

The Squadron now in one place, flying continued with trials on behalf of the Bomber Command Development Unit. Hereinafter always known, as (BCDU). The ORB does not mention the purpose of these flights, although it lists every sortie. However, we know from various sources that, cross country navigation trials and bombing exercises on the Lincolnshire ranges were included.

During this time, anyone working on the airfield, would have noticed a lone Valiant parked at the western end of the airfield, close to the, then, very mysterious Bomber Command Armament School (BCAS). To add to the mystery, the aircraft WP201, was frequently surrounded by wooden screens. A good way, one might have thought, of drawing attention to it. However, such was the naivety of us young lads, and the secrecy of the times, that no one asked too many questions about this. Or what the armourers and carpenters, who began to arrive in our block from a place called RAF Aldermaston, and who worked at BCAS were up to.

We now know BCAS was a polite euphemism for the establishment that developed and tested the designs for the British Nuclear Weapons programme. WP 201 was dropping inert versions of the bomb, known as Blue Danube, in to the sea at the Orford Ness range. We were, I recall, granted a look at the bomb installed in a Valiant before the Maralinga test. But, even then, the officer showing us around could not bring himself to refer to the big shiny thing as a nuclear bomb, referring to it only as the weapon for which this aircraft was designed. I think it fair to say that, by that time, most of us had twigged it.

In January 1956, the Squadron ORB noted that 1321 flight, which consisted of one Valiant (WP201), was to become ‘C’ flight of 138 squadron. At that time, it appears that there were two crews involved, those of the flight commander Sq/Ldr Roberts, and Flt/Lt Bates. From what can be gleaned from the ORB, the 1321 training activities continued, with 138 crews taking part. In May of 56, ‘C’ flight became 49 Squadron under the command of S/Ldr Roberts. By this time some 138 crews were posted to 49 including S/Ldr Ted Flavell, who was destined to carry out the first airdrop nuclear test later in the year.

The ORB notes various coming and going of aircrew although, of course, practically no mention of ground staff. Most of the goings appeared to be to 49 squadron, with S/Ldr Steele and his crew disappearing, along with S/Ldr Millett. Also amongst the disappeared was F/O O’Connor, Jock Browns original co-pilot who, after a captains course at Gaydon, finished up on 49 Squadron. All of these officers subsequently carried out live weapon drops during the Grapple trials at Christmas Island.

The ORB makes reference to routine flying duties throughout the spring and summer of 1956, although there is mention of what appeared to be a day trip to Luqa by the CO. This was the first visit of a Valiant to Malta, and in view of what was to come later in the year, may have had some other significance.

What was to come was, of course, the Suez adventure, campaign, fiasco, call it what you will. Without getting involved with the rights and wrongs of what was at the time, and to some people still is, a very controversial episode, it is amusing and informative to look back. It is accepted by all parties now, with the release of all the documents, that Suez was an attempt by the British, French and Israeli governments, to dispose of the Egyptian Leader Abdul Gemmel Nasser and regain control of the Canal Zone.

The plan was that Israel would attack Egypt, and the Anglo French authorities would issue an ultimatum to the warring parties to cease or we, the allies, would intervene to stop them. Of course, the real reason was that Nasser had had the temerity to nationalise the Suez Canal, in which the Brits and the French had both financial and strategic interests. The outcome is well known, we omitted to ask the Americans permission, they took umbrage, the Russians rattled their Sabres, and the enterprise collapsed. Taking with it a great deal of British power and prestige

I include this potted history, because there were signs, even then, that things were not as they were later portrayed in the press. I seem to remember us doing things to the aircraft, such as installing Widow dispensers and high-level visual bombsights, some time before we went. I also recall practice bombing with these sights over the Jurby range off the Isle of Man. This was before there was any attack on Egypt by Israel.

Regardless of all this, we were told shortly before departure, that we were to be detached to Malta. Which is how it came about that we assembled in the hangar on, I seem to recall, a Sunday morning wearing, as instructed, our pyjamas under our working blue and denims. We were issued with dog-tag identification discs, and loaded into Shackletons. No seats of course, thirty five of us sitting on the floor for take off, for what turned out to be a very long, bumpy and uncomfortable flight of over eight hours to Luqa.

On arriving at Malta and going to work, the first indication that something was up was when the aircraft were bombed up with what appeared to be, even to me, ten live one thousand pound bombs. An even larger clue, was the appearance of Jock Brown and his crew wearing side arms and emptying their pockets, to ensure that they were not carrying anything that could identify their base of operations.

Jock and his crew set off with their customary dispatch and we were told by Chief Tech Keen to be on the airfield in approximately five hours time to see the aircraft in. Still no explanation of what was going on. So we all meandered off to enjoy the delights of Luqa transit camp, and to get early tea. About two hours after take off, a Tannoy message summoned all 138 Squadron crews to their dispersals. When we got there Valiants were landing and taxiing. Something was obviously amiss.

What was amiss, was that whilst the aircraft were in the air, 10 Downing St was advised that there were American civilians on Cairo West airfield, one of the primary targets. It is alleged that when he received this news Anthony Eden said to Anthony Head, who was the War Minister, “get those aircraft back and I’ll make you a Duke”.

In the event, that proved more difficult than it seemed. A combination of poor HF radio, and strict radio silence procedures, meant that it was difficult to contact the aircraft. When contact was made, crews were dubious about the authenticity of the message. S/Ldr. Clifton, who took part in the raid, recently stated in a letter to FlyPast magazine that is was not until he received a message in plain language from Cyprus, from an officer he recognised, that he was satisfied the recall was genuine. That officer may have been Group Captain John Woodruffe, the Officer Commanding Wittering at the time, who was in overall charge of the air operations at Suez and was based in Cyprus for the event.

For our part, Jock Brown told us that he did not get a recall message. His aircraft (WP215), had the old, unmodified, HF aerial and it was only when he saw contrails going in the wrong direction that he realised something was up.

So the campaign did not get of to the start hoped for, however, other sorties went better and there was fairly intense bombing activity for the next few days. Eventually, the mission was completed and suddenly, in the space of a morning, all of the Valiants on the island were gone. This was the return of all the Valiants from 138, 148, 207 and 214 Squadrons.

One of the reasons for the abrupt departure was probably due to Mr Khrushchev making belligerent comments about sinking Malta with rockets, and it probably seemed like a good idea to get the shiny new V Bombers off the island. Needless to say, the ground crews were airlifted out two days later, having spent the two intervening days watching the Royal Artillery installing and practicing with anti -aircraft guns.

The Suez trip was portrayed, at the time, as a rousing success for Bomber Command and proof of the effectiveness of the V Bombers and their crews. Lord Tedder addressed us at Wittering and told us what a grand job we had done, and we should be proud of ourselves.

In fact the truth was very different. We now know that, in the main, the bombing was ineffective and inaccurate. The civilians of Cairo were treated to varied doses of bombs, which were supposed to fall on military targets, but did not. This was not due to a lack of skill or bravery on the part of the aircrew, but was the result of several factors. The bombing was conducted from great altitude, as the Valiants were considered vulnerable at low level. There was no suitable bombing aid; Gee did not cover the Mediterranean. Only a couple of aircraft were fitted with NBS, an upgrade of the wartime scanning radar H2S, which itself was far from reliable.

On the ground, servicing equipment was sparse. Someone forgot that the RAF did not use self-propelled ground equipment, and there were no tractors available. Try pushing the old Rolls Royce PE set across an airfield, at night, when your aircraft is loaded with bombs and waiting to start its engines.

In general, the discovery was made that the V Bombers, and indeed the Canberras were not suited, or capable, of effective action outside of Europe. As a result of that, steps were taken to remedy the problem. Later members of the squadron would enjoy the benefits of that discovery, as they went on various operations to exotic destinations. Operation Sunspot and Lone Ranger exercises all commenced post Suez.

Almost immediately after the return from Luqa, several aircraft were detached there again. The Squadron had several aircraft and crews at Luqa over Christmas 56. The ORB notes that aircraft and aircrews were rotated over the period, but there is no mention of ground crew.

During the period of 1956, the only reference to ground crew in the ORB, refers to Corporal Pop Morley, LAC Bob Maley and AC Rupert Nanton representing Wittering at the Bomber Command athletics championships, and Pop Morley going on to represent the Command. Tom Bullamore, an Air Radar Mechanic, also got a mention for his athletic prowess. I seem to recall Tom B and Pop Morley having this strange pastime, but I have no recollection of Bob Maley or Satch Nanton displaying these tendencies.

When ground crew are mentioned, it tends to be for displaying ‘jolly good sporting prowess’ at footer or such like. Or, in a slightly patronising sense such as, “ the ground crews did a fine job, working long hours in difficult circumstances”. Reading these records one is struck by the feeling of the, ‘them and us’ attitude that prevailed in those times.

Having said that, it has to be said that the relationship between air and ground crews was quite relaxed, and there was evidence that there was a positive attempt by the management to foster this situation. Parties were organised at Christmas, at which officers would turn up. In the case of my own crew, Jock Brown organised a memorable evening at the Haycock at Wansford for the air crew and ground crew, at which excess was the order of the evening.

In June 57, the Squadron won the RAF bombing contest, with W/C Oakley’s the top crew. In July, the CO and Flt/Lt Mather, took part in the Strategic Air Command Bombing Contest in the USA. They were part of a contingent from Bomber Command, which included a couple of Vulcans as well as Valiants from Marham. Although the Valiants did reasonably well, a Marham Valiant coming 11th out of ninety crews overall, there was disappointment in political circles. The P.M., Harold Macmillan, is quoted in a note to the Secretary of State, as saying that we used to take pride that we were so much better than the Americans at these things. Yet here were the Valiants coming 27th out of 45 and the Vulcans, that are supposed to be so much better, doing much worse. The Secretary of State, George Ward, pointed out the problems our crews had and in later contests the RAF did much better.

It was on this expedition to the United States that Gp/Cpt Woodruffe, the very popular and respected Station Commander of Wittering, was killed when the B47 in which he was a passenger crashed.

In November 1957 W/C Oakley relinquished command of the squadron. He was succeeded by W/C S. Baker. W/C Sidney (Tubby) Baker was a much-decorated WW2 veteran, whose arrival at the Squadron as C/O, created a shudder of change amongst Squadron personnel. A ‘working blue’ parade was held on his first day as C/O at which there were apparently adverse comments about the turn out of the troops. Expensive trips to the clothing store were the result. It was as well that this regime was not in force during the squadrons’ earlier years, as it would have been likely that a quarter of the ground staff did not possess a full set of working blue. This commenced the era of the “Cats Arse”.

Wing Commander Baker had an expression “you cannot win” (NULLO MODO VINCES), which both air and ground crew became familiar with, and referred to any attempt to circumvent his wishes. Certainly his time with the Squadron was marked by considerable activity. The ‘cat’s arse’ was now to be found in the most unlikely places. Nobby Unwin made a superb lino-cut, highlighted with black shoe polish, and this was carefully inserted into the floor covering in front of Tubby’s desk. The reasoning behind this was, anyone up before the C/O was standing above the cat. In January 1959, Nobby managed to ‘acquire’ a block of sandstone, from a Maltese building site, and spent the next few days carving the cat into it. W/C Baker was not amused and ordered it destroyed. Luckily, Jock Brown was flying back to Wittering the next day, and suggested it be placed in the Pannier. Thus, the cat returned to Blighty, to commence a long and illustrious career.

At this time the ORB notes that the Squadron had a strength of ten aircraft, occasionally eleven. It appears that an additional two, to take account of the work carried out on behalf of BCDU, such as the Rocket Assisted Takeoff trials augmented the normal strength of eight aircraft. This afforded tremendous entertainment for the ground-crews, as the aircraft, after taking off, were required to circle the airfield and drop the rocket motors onto the grass. Since each motor was very expensive, they were equipped with a parachute, and when one came down with an unopened ‘chute’ there was a loud explosion, as the remnants of the fuel exploded. Other motors were dropped, ‘inadvertently’ into the large pond on the northern perimeter of the airfield.

In April ’59, the Squadron received two ‘Mini-Mokes’ to be tested as ‘on-board’ transportation for aircrew on ‘Lone Rangers’. They fitted, very nicely, into the bomb-bay but by carrying them, a spares pannier had to be forfeited. They did however, provide hours of entertainment for the groundcrew. After receiving clearance from Air Traffic one could observe these vehicles, containing six or seven occupants, tearing around the peri-track.

In June 59, this arrangement was formalised by the creation of C Flight, to handle the BCDU work. The ORB notes that three aircraft were allocated for this work, WZ400, XD872 and, if the ORB is to be believed,WP214. During this period, and indeed for most its later life, the Squadron had a strength of between forty and forty-five officers, and one hundred and ten to twenty other ranks.

By now, 1958, the Squadron was engaged much more in its basic role as a member of the medium bomber force, whose prime function was to airfreight large packages of plutonium and other rather dangerous substances to the Soviet Union. With the benefit of hindsight, this may not seem to have been very sensible occupation or good use of the taxpayers’ money, but in the climate of the time it was deemed necessary.

So it was that 138 crews qualified for the select status that showed them capable of carrying out this fearful work In November 59, the ORB notes that Messrs Baker and Clifton had achieved select star status, which put them at the top of the bomber command tree. It’s fair to say that several other crews achieved this status, but were not always listed in the ORB.

In order to reach the standard of readiness necessary for the deterrent to be credible, the Squadron practised dispersal to other airfields, including Gaydon and Leeming. It is interesting to note the detail which the movement orders for such dispersals went into. Listing in some detail the times of transport for the ground crew and arrangements for meals etc. It also included diagrams, displaying where particular pieces of Ground Equipment were to be placed in the trucks for transportation.

During 1958, other noteworthy events included SAC Tom Bullamore winning the camp 440 yards championship, and S/Ldr Collins, B Flight commander, leaving the Squadron to take up an appointment with BCDU. It was also noted in the ORB, that this officer had set a record time when flying from Ottawa to Marham earlier in the year. The ORB also mentions that F/O Stafford, an Air Electronics Officer, became the first RAF officer to complete one thousand flying hours in a Valiant. Cynics might conclude that he must have made gallons of soup in that time.

During 1958 and 1959, Squadron aircrew took part in ‘Lone Ranger’ trips to various destinations including Salisbury Rhodesia, Canada, the United States and Malta. One assumes the trips were divided out on an “I’ve been there before, now its your turn” basis.

During 59, several long service pilots left the Squadron. Flt/Lt Mather, an original A flight captain, went off to BCDU, and S/Ldr Burberry left for a Victor course at Gaydon. However the high point of the year must have been a detachment of four aircraft and crews to Butterworth, Malaya it. Presumably this was a flag waving, as well as training exercise. The Malaya confrontation was going on at the time and the sight of four shiny white V bombers would have had a sobering affect on our adversaries.

The annex to the ORB goes into great detail on the travel arrangements, both for aircrew and ground crew, with much listing of next of kin and religious affiliation. It also mentions overseas pay ranging from two shillings and nine pence a day for Officers, to one and sixpence for the troops. Some of the names listed, as ground crew, will have redolence to the friends of 138, such as Sac’s Unwin and Roe, J/T’s Craze, Priest, Jones and the notable missing, such as Messrs Soffe, Auburn and many others. It is worth noting that by now the Squadron was clocking up between two hundred and fifty and three hundred flying hours a month. Anything over three hundred hours was treated with great satisfaction in the ORB. For comparison, in its’ early days, the Squadron would be lucky to achieve one hundred and fifty hours a month.

The first of April 1959, is a date that lives in infamy for the ground-crews of the Squadron. After extensive retraction tests in the hangar, WP402 was returned to the dispersal to await an air-test. This was to be conducted by the Squadron C/O, Tubby Baker. After taking his place in the Captains’ seat, he informed the Crew-chief that the ‘emergency up’ had not been reset. The crew-chief, C/T Len Owen, asked if this could not be reset once the plane was airborne and was told by Baker that it must be reset immediately. The impossible happened at this point, and the ‘emergency up’ was activated. The aircraft settled, very gently, onto it’s nose and PANIC set in. The rigger, Bill Craze, ran to the flight office to report the disaster and was told, by F/S George Barman, to “Piss off, I know what day this is”. Thus, the Valiant was not merely the first to go operational, drop weapons in anger, drop Britains’ Nuclear Deterren, but became the first V-Bomber to Curtsy.

In 1960, the Wittering runway had to be resurfaced and flying was undertaken from Cottesmore between March and June. Just before that S/Ldr Clifton, now A Flight Commander, left to take up the job of RAF Liaison Officer at Offutt Air Base, Nebraska. In early 1960, Tubby Baker completed his tour and was replaced by W/C H Chinnery. The Squadron returned to Wittering, where it was joined by No 7 Squadron, from Honnington.

In August, a 7 Squadron aircraft (XD 864) crashed just after take off and the ORB notes that one of the crew (all killed), was a 138 Pilot, Flt/Lt W Howard, flying as co -pilot on that particular evening.

During the remainder of 60 and 61, the Squadron continued its’ flying schedule much as before. There are the usual comings and goings. Flt/LT Don Briggs left for Gaydon in September 61, to work as instructor on Victors.

The ORB, in February 62, announces that a memo has been received from Bomber Command informing them that the Squadron will be disbanded with effect of Midnight on the 30th March. It goes on to say that, in the interim, personnel would be receiving new postings and that aircraft and equipment would be redistributed where appropriate. And that was that.

So ended 138 Squadron. The first, and certainly in view of the old codgers who served on it, the best V bomber Squadron.

There was, however, a postscript in the final ORB which read something as follows: “Permission has been granted for two aircraft to take part in the Bomber Command Bombing and Navigation contest on the 9th and 10th of April 1962. The crews will be those of W/C Chinnery, and Flt/Lt Brown”. So Jock Brown, the longest serving 138 pilot, flew on its last sortie. It was probably Jocks’ last flight for the RAF as he is listed as retiring in April 1962.

So what was going on that caused the demise of 138? Well to begin with it had served for seven years, which originally was to be the allotted span for a V bomber tour. Secondly, the Air Force was now equipped with Vulcans and Victors which, in Macmillan’s words, were supposed to be “so much better”. However the real truth was probably more complicated.

When Gary Powers’ U2 was shot down by a Surface to Air Missile in 1959, it really signalled the end for the idea of an airborne high altitude nuclear deterrent. Although, of course, no one was going to say so at the time. The RAF’s response to this had been to call for the Mark 2 Vulcan and Victor, which, for a lot of expense, could fly a little higher and faster than the Mark Ones. However, the Mark 2 Valiant, which was flying before the Mark One Vulcan and Victor were in service, comfortably out -performed the B2 Vulcan and Victor. Most importantly, this aircraft, which was designed to operate at low level was cancelled. The Air Force had ordered 17 B2 Valiants. WZ 389 to WZ405 were supposed to have been B2’s, but were subsequently changed to B1’s.

The powers that be had also been persuaded to allocate some Valiants to Strategic Air Command Europe. This would give the RAF access to some American nuclear weapons. British versions of these things were a trifle thin on the ground in those days. Marham was chosen as the station where these aircraft would be stationed. Presumably because it had nuclear storage facilities suited to American needs from earlier days. Therefore a wing was established at Marham, which became the Tactical Bomber Force, consisting of 148, 207 and 49 Squadron. These were to be the poor sods that had their aircraft camouflaged and went down to low level flying. 214 Squadron, the tanker division, was also stationed at Marham. Meanwhile 7 Squadron and 138 remained at Wittering, as the sole remaining part of the Valiant Medium Bomber force, until the arrival of the Victors of 100 and 139 Squadrons brought about their retirement.

As we all know, in 1965 the entire Valiant force was retired due to cracks being found in the main spars. There have been lots of discussions about the whys and where-fore’s surrounding this decision, but in truth, there seems to have been little alternative. Cracks had been found on Valiants before the major incident with WP217 at Gaydon. There had been unexplained accidents, such as WZ 363 at Binbrook. The problem was almost certainly not due to low level use. Aircraft on 543 Squadron, which operated at high altitude, were found to be just as liable to cracking as the low level machines.

The truth is, that the whilst the Valiant may not have been as advanced technically as it’s two competitors, the materials from which it was made were current state of the art. Metal fatigue was not understood, as it was to be later.

So ended the Valiant. Try and think of another government project that was completed so successfully. On time and on budget, and that worked, to quote Bill Craze in another place, “straight out of the box”. Without taking anything away from the Vulcan, a great Air Show aircraft, or the Victor, a wonderful tanker. As an overall project, the Valiant wins hands down.